Plant-mediated rifampicin treatment of Bemisia tabaci disrupts but ... - Nature.com

Abstract

Whiteflies are among the most important global insect pests in agriculture; their sustainable control has proven challenging and new methods are needed. Bacterial symbionts of whiteflies are poorly understood potential target of novel whitefly control methods. Whiteflies harbour an obligatory bacterium, Candidatus Portiera aleyrodidarum, and a diverse set of facultative bacterial endosymbionts. Function of facultative microbial community is poorly understood largely due to the difficulty in their selective elimination without removal of the primary endosymbiont. Since the discovery of secondary endosymbionts, antibiotic rifampicin has emerged as the most used tool for their manipulation. Its effectiveness is however much less clear, with contrasting reports on its effects on the endosymbiont community. The present study builds upon most recent method of rifampicin application in whiteflies and evaluates its ability to eliminate obligatory Portiera and two facultative endosymbionts (Rickettsia and Arsenophnus). Our results show that rifampicin reduces but does not eliminate any of the three endosymbionts. Additionally, rifampicin causes direct negative effect on whiteflies, likely by disrupting mitochondria. Taken together, results signify the end of a rifampicin era in whitefly endosymbiont studies. Finally, we propose refinement of current quantification and data analysis methods which yields additional insights in cellular metabolic scaling.

Introduction

Whiteflies, especially those of the Bemisia tabaci species complex, are some of the most important insect pests worldwide due to their invasiveness and transmission of plant viruses causing hefty economic losses1,2. At the same time, management of whiteflies and whitefly borne viruses is challenging due to their ability to attain insecticide resistance or efficient virus transmission before control methods show effects3,4. Diverse strategies are being investigated for more effective and environment friendly whitefly management methods, one of which is trying to exploit bacterial endosymbionts of whiteflies5. This idea is as old as the discovery of the critical role that endosymbionts play in enabling phloem feeders to survive on a very imbalanced diet6. In a bigger picture, whitefly holobiont is one of the most diverse among all insects7. Untangling the interactions between the organisms would deepen our understanding of microbial communities which through complex, context-dependent interactions with their host allow colonization of a unique ecological niche and provide adaptive plasticity in changing environments8.

The whitefly (B. tabaci) holobiont is one of the most diverse among all insects. B. tabaci harbours an obligatory bacterial endosymbiont alongside being host to zero to multiple facultative endosymbionts. The obligatory endosymbiont Candidatus Portiera aleyrodidarum synthesize and complement essential amino acids, vitamins and carotenoids that are lacking in the whitefly genome repertoire and are also deficient in the phloem sap9,10. Prevalence and diversity of bacterial secondary endosymbionts belonging to the genera Arsenophonus, Cardinium, Fritschea, Hamiltonella, Hemipteriphilus, Rickettsia, and Wolbachia vary across the different B. tabaci species and are not congruent with the phylogenetics of their whitefly host11. Reports of new facultative endosymbionts within B. tabaci have been rare in recent years indicating that the genetic diversity has been well explored. Roles of these facultative endosymbionts are however much less clear. They provide evolutionary advantage in certain environmental conditions while being neutral or detrimental in others, as for example it is evidenced by dramatic shifts of Rickettsia prevalence in B. tabaci populations over time reported by Cass, et al.12. Therefore, they can together be described as context-dependent modifiers of whitefly biology. Their presence and composition in whitefly populations varies over time and space in a so far largely unexplained manner5. Understanding the roles of facultative endosymbionts is essential in predicting how whiteflies will behave in new environments such as with changing climate and how we can manipulate them for the control of whiteflies and whitefly borne viruses.

Studies of endosymbiont roles have been hindered by the difficulty in obtaining whitefly populations with different endosymbiont compositions5. Facultative endosymbionts are especially difficult to study due to their conditional effects on the biology13,14. The environment and whitefly genome simultaneously affect both endosymbiont composition and whitefly biology directly. Separating the effects of whitefly genetic background, the environment, and endosymbiont community on the overall whitefly behaviour and fitness is challenging and necessitates whitefly populations with identical background but different endosymbiont composition. The main method explored so far for selective elimination of whitefly endosymbionts, and for probing the effects of modified endosymbiont densities, is the use of antibiotics. There are over a dozen published studies involving antibiotics and whitefly endosymbionts15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. The antibiotics were used for two purposes: to either attempt to selectively eliminate secondary endosymbionts, or to temporarily reduce their densities with the hope of observing the effects which lower densities have on the insect biology.

The two most common methods of elimination of symbionts are the delivery of antibiotics supplemented in water sucrose solution through parafilm-based artificial feeder or the delivery through the plant phloem. Recently, a selective and stable elimination of whitefly endosymbionts have been claimed using the phloem delivery method, although other studies report mixed results15. Nevertheless, a move from delivery of antibiotics in water sucrose solution to delivery through the plant phloem seems to result in more efficient and precise manipulation of the endosymbiont community. This is hypothesized to be the case because plant phloem delivery method is able to deliver antibiotics over longer periods of time, alongside natural diet of whiteflies.

Several antibiotics have been tested on whitefly endosymbionts so far, with their selection mostly being guided by the patterns of antibiotic sensitivity in distantly related culturable bacteria23. Tested antibiotics include rifampicin, ampicillin (ampicillin trihydrate), tetracycline (oxytetracycline hydrochloride), chloramphenicol, penicillin, and antimicrobial enzyme lysozyme. Over time, rifampicin emerged as the most potent and widely used, with majority of the studies using only rifampicin15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. Published studies reveal the pattern of poor selectivity of these antibiotics between different endosymbiont species present in whiteflies, although there are definitive differences in their sensitivity to antibiotics15. Major reduction of facultative endosymbionts without substantial reduction of the primary endosymbiont is also not possible. Differential response between the obligatory Portiera and a secondary endosymbiont was only reported for Hamiltonella which showed faster reduction rates, resulting in a possibility of eliminating Hamiltonella without eliminating Portiera15. Successful elimination of Hamiltonella using rifampicin was also reported using the artificial diet method by Su, et al.29. Rickettsia and Cardinium show similar response to rifampicin as Portiera, while use of tetracycline resulted in higher reduction of Cardinium compared to other endosymbionts15. Rate of reduction of Wolbachia and Arsenophonus in comparison to Portiera were not robustly tested to date. Other secondary endosymbionts, Fritschea and Hemipteriphilus, are rare in whiteflies and have not been included in antibiotic experiments so far.

The direct effect of antibiotics on whiteflies is another major problem with their use in the studies of bacterial endosymbionts. Negative effects have long been speculated but never demonstrated to date16,19. For example, the binding site of rifampicin is the bacterial DNA-dependent RNA polymerase30, but ability to bind to mitochondrial RNA polymerase in eukaryotes has been demonstrated in the rat liver cells31. The direct negative effects of rifampicin in whiteflies could limit its usability in studying roles of endosymbionts and their effects on whitefly biology as it is impossible to distinguish them from the effects of reduced endosymbiont densities.

The present study aims to re-evaluate and quantify the effects of rifampicin on the obligatory Portiera, and two facultative endosymbionts, Rickettsia and Arsenophonus, using the latest antibiotic delivery method. We advance the method of whitefly endosymbiont density quantification by introducing a normalization method, with the aim of reducing the measurement variability and to probe the relationship between nuclear DNA (nDNA) content, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) content, and endosymbiont densities. Further, we evaluate the feasibility of selective elimination of these facultative endosymbionts and attempt to pinpoint the cause of the challenges. Finally, we test the hypothesis that whitefly mitochondria are negatively affected by rifampicin and ask the question if antibiotic experiments can still yield useful insights into whitefly-endosymbiont interactions.

Materials and methods

Plant material

For whitefly rearing and antibiotic experiments, tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) plants of the cultivar 'Moneymaker' were grown from seed (Kiepenkerl, Bruno Nebelung GmbH, Everswinkel, Germany) in an insect-proof cage (50 × 50 × 50 cm) at 22 °C, 50% RH and photoperiod of 12L:12D under Valoya C65 lights with NS12 spectrum (Valoya, Helsinki, Finland). Plants potted in 5 l pots plants were fertilized weekly by irrigating with 200 ml of Peters Professional Allrounder (Dublin, OH, United States) water soluble fertilizer at the concentration of 2 g/l.

Insect colony

The laboratory whitefly colony was established by introducing eggplant leaves infested with pupal stage of B. tabaci MED to the insect proof cage containing a tomato plant. The infested leaves were collected in October 2019, from eggplant grown in a greenhouse in south-eastern Sicily (Vittoria, province of Ragusa, Italy; 36.97134° N, 14.424505° E). The petioles of leaves were kept in water in the cage for 48 h to allow eclosion of whitefly adults. Established colony was maintained on tomato for over ten generations before being used for any experiment. Colony was maintained by regularly transferring whitefly adults to new tomato plants.

Whitefly identification

Whitefly DNA was extracted and PCR was performed as described in Milenovic, et al.32. In short, DNA was extracted from ten whiteflies individually, and for each a fragment of mitochondrial Cytochrome Oxidase I gene (mtCOI) was amplified using Q5® Hot Start High-Fidelity 2X Master Mix (New England Biolabs, MA, United States), and sanger sequenced. Obtained sequences were subsequently aligned with the mtCOI reference dataset as published by Boykin, et al.33 using MAFFT v7.49034 with FFT-NS-I method and manually inspected for potential errors and trimmed to the same length (657 bp). The most suitable evolution model was determined to be GTR + I + G using MrModeltest v2.435. Selected model was used to perform Bayesian inference phylogenetic analysis using MrBayes v3.2.7a36,37,38. Two independent runs of Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) were performed with 64 chains and sampling/diagnostic frequency of 1000 until average standard deviation of split frequencies fell below 0.01, which happened after 28,087,000 generations. Bayesian posterior probabilities were subsequently calculated and are presented for each node of the phylogenetic tree. The burn-in fraction was set to 25% for MCMC, SUMP and SUMT commands. The resulting tree was drawn using FigTree v1.4.439. The process was repeated once again, and the resulting tree was compared to the first run pair to confirm that the analysis was not trapped in the local optima. Whitefly biotype was then identified.

Endosymbiont identification

Whitefly endosymbionts were detected and identified by means of PCR amplification and sequencing of a portion of 16S rDNA gene of each endosymbiont described in whiteflies to date. Amplification was performed using Q5® Hot Start High-Fidelity 2X Master Mix (New England Biolabs, MA, United States). A PCR consisted of 30 s initial denaturation at 98 °C, followed by 35 cycles of 7 s denaturation at 98 °C, primer annealing for 20 s and extension for 20 s at 72 °C, followed by final extension of 2 min at 72 °C. Each endosymbiont was targeted using primer set at the optimal annealing temperature as described in Table 1. Amplicons from positive reactions were sequenced using Sanger sequencing method. Raw sequencing reads were manually trimmed to remove low quality bases. Forward and reverse sequences were aligned and assembled using CLC Main Workbench v21.0.1 (QIAGEN, Aarhus, Denmark). Sequences were identified by performing BLAST search at NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) using default settings. In case of Portiera and Rickettsia, BLAST search was enough to identify the phylogenetic group as there was 100% sequence identity with sequences previously subjected to phylogenetic analysis by Kanakala and Ghanim11. Arsenophonus sequence did not yield identical match. To determine the phylogenetic placement, Arsenophonus sequences from the study of Kanakala and Ghanim11 were downloaded, as well as 10 other top BLAST hits, and phylogenetic analysis was performed using the same method as for the identification of whitefly biotype described above. Multiple sequence alignment was trimmed to the same length (616 bp). The best model was identified to be HKY + G.

Endosymbiont localization

Localization of detected endosymbionts was performed using fluorescence in situ hybridization technique (FISH), using a modified protocol of Gottlieb, et al.40. Whitefly adults and nymphs were collected from the plant and immediately fixed in Carnoy's fixative (6:3:1 mixture of chloroform, ethanol and glacial acetic acid) overnight. Whitefly eggs were collected and fixed together with a small piece leaf tissue to which the eggs were attached, which allowed easier manipulation of the sample. Fixation was followed by thorough wash in 100% ethanol and overnight decolourization in 6% alcoholic H2O2 solution. Specimens were washed again three times in 100% ethanol, and 3 times in PBST solution (1X PBS with 0.3% Triton X100). Next, specimens were washed 3 times in probe-free hybridization buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 0.9 M NaCl, 0.01% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 30% formamide, PCR-grade H2O) and incubated in the same buffer for 15 min. Buffer was then replaced with the same buffer supplemented with FISH probes (5' Cy3-TGTCAGTGTCAGCCCAGAAG 3' and 5' Cy5-TCCACGTCGCCGTCTTGC 3' for Portiera and Rickettsia, respectively) at 100 pmol/ml concentration and hybridized overnight in the dark at 22 °C. To reliably detect Arsenophonus which is present in lower densities, a doubly labelled FISH probe (5' Cy3-TATCGCAGGAGAAAAGTCTG-Cy3 3') was used with the same hybridization protocol as for the other endosymbionts41. Post hybridization wash was carried out by washing 3 times with probe-free hybridization buffer this time supplemented with 0.1 mg/ml DAPI as a DNA counterstain. All steps were performed in 200 µl sterile PCR tubes. Whiteflies were then mounted using hard setting VECTASHIELD® Vibrance™ Antifade Mounting Media (Vector Laboratories, Inc., United States) and observed under Zeiss LSM 880 confocal laser scanning microscope. The same protocol was followed for whitefly eggs, nymphs and adults. In total 5 eggs, 7 nymphs and 9 adults were imaged. Finally, as an independent supplement to qPCR quantification, nine antibiotic treated individuals of different developmental stages were also subjected to FISH followed by laser scanning confocal microscopy in the same way.

Antibiotic treatment

Plants used to deliver antibiotic solution were established by rooting tomato side shoot cuttings with five fully developed leaves in an insect-proof cage (50 × 50 × 50 cm), kept at the same conditions as the whitefly colonies. Side shoots were cut and immersed into an opaque 250 ml glass bottle containing water solution with 1 g/l Peters Professional Allrounder fertilizer (ICL Specialty Fertilizers, Ohio, USA) and kept until extensive root system developed. A total of six plants were established. At this point, about 50 unsexed whitefly individuals per plant were introduced to the cage. Whitefly adults were subsequently removed after one week. When the whitefly eggs were close to hatching, water-fertilizer solution in five out of six plants was replaced with water solution containing 25 mg/l of rifampicin antibiotic (AppliChem GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany). Water-fertilizer solution of the sixth plant was replaced with water to serve as a negative control and moved to a different cage. During the experiment, the loss of solution due to uptake by the plant and evaporation was replenished daily by adding water. After 10 days, the solution was replaced entirely with fresh antibiotic solution, or watery for the treated and control plants respectively. The treatment continued until the eclosion of adults. At this point, whitefly adults were collected by aspiration, sexed, and individually stored in 200 µl of ethanol until DNA extraction. Additional adults were collected in the same way from the laboratory population, not subject to any experiments.

Endosymbiont quantification

DNA extraction was performed the same way as for the whitefly identification described above. Number of analysed individuals was 48 females and 48 males in the antibiotic treated group, 24 females and 16 males in negative control group, and 24 females and 24 males in the rearing colony group. Relative quantity of whitefly endosymbionts was determined using TaqMan probe method of quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) using Takyon™ Low ROX Probe 2X MasterMix dTTP blue reagents (Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium). Multiplex primer/probe sets were designed for Portiera and Rickettsia, one set for Arsenophonus, and two additional primer/probe sets were designed targeting whitefly nuclear DNA (portion of Actin gene), and mitochondrial DNA (portion of COX1 gene) to enable normalization and to investigate the effects of rifampicin on whitefly mitochondria. Whitefly nuclear DNA primers were design based on the α-actin NCBI GenBank sequences KJ913697.1, KC161211.1 and MN738077.1. Mitochondrial DNA, Portiera, and Rickettsia primers and probes were designed based on NCBI GenBank sequences MH205753, CP003835.1 and CP016305.1 respectively. Arsenophonus primers and probes were designed based on the alignment of all available Arsenophonus sequences with at this time still unpublished Arsenophonus genome sequencing reads. Probes were purified using RP-HPLC method and primers desalted. All qPCR primers and probes used in this study are presented in Table 2. Standard curves for each target were constructed based on 10-step 1:2 serial dilution of a sample with highest DNA concentration as determined by spectrophotometer, with three replicates per point. As the total number of samples was 184, the samples needed to be split between two 96-well plates. To account for any variability between runs, each treatment group was equally represented in both plates. As an additional check, due to the impracticality of running all 10-point serial dilution samples on all plates for all targets, the consistency between runs was verified by including simplified 3-point dilution of the same sample on all plates. Finally, a negative control sample was included in all plates. The assay was performed on ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA). Threshold cycle (Ct) values were determined using QuantStudio™ Real-Time PCR Software v1.3 and exported to an XLS file for further analysis. Threshold was set to the same value for all targets across the experimental runs.

Quantification of rifampicin

To test the validity of rifampicin delivery through the plant and into the insect body, a separate assay was performed to detect and quantify the antibiotic in both plant and insect tissue. Rooted tomato side shoots were immersed in opaque 250 ml glass bottles containing a 25 mg/l rifampicin water solution. About 150 whitefly adults were introduced 72 h later in a clip cage clipped to a single tomato leaflet. At this point first tomato leaf samples were collected, weighed, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until processing. 96 h later, whitefly adults were removed, counted, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Tomato leaflets to which whiteflies were restricted were also collected, weighed, and stored in the same way. Separately, 230 whitefly individuals were weighed to determine the average weight of unsexed whitefly adult.

Rifampicin was extracted from the leaf and whitefly samples using LC–MS grade acetonitrile (ACN) as follows. Samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground in 2 ml tubes using bead mill homogenizer with two 3 mm stainless steel balls for 1 min at the frequency of 30 Hz, with liquid nitrogen pre-cooled tube holders. Samples were then briefly centrifuged, acetonitrile was added to the tubes, and the entire sample was transferred to a glass test tube. Steel balls were removed using a magnet and washed with acetonitrile which was also added to the sample. Samples were then placed in an ultrasonic bath Elmasonic S300 (Elma Schmidbauer GmbH, Singen, Germany) for 15 min. Liquid was aspirated and filtered through a 0.45 µm PVDF syringe filter into a new glass vial. Pellet of solid parts from the tomato leaf samples was subjected to a second round of extraction by adding 2 ml of acetonitrile and sonicating for 15 min, followed by aspiration of the supernatant and filtering, and was added to the extract from the first round. Samples (about 5 ml total per sample) were then evaporated at 30 °C with 1–2 l/min airflow until dry using TurboVap® LV evaporator (Biotage Sweden AB, Uppsala, Sweeden) and reconstituted in 2 ml of 1:10 ACN: H2O. Samples were diluted 1:200 and 1:40,000 in 1:10 ACN: H2O and placed in the autosampler of the LC–ESI–MS/MS system Agilent HPLC (Agilent, Santa Clara, USA) coupled with a QTRAP 4500 MS/MS (AB Sciex, Framingham, USA) for quantification of rifampicin. An online-SPE injection method (0.9 mL injection volume per sample) was used. Online extraction of the water samples was performed using trapping column Hypersil Gold, 20 × 2.1 mm and 12 m particle size (C18 Selectivity phase, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Separation of rifampicin was performed using Luna Omega C18 Polar column (100 × 2.1 mm with 3 m pore size) (Phenomenex) in positive ionization mode. A mass spectrometry grade rifampicin was used for preparing the standards. A seven-point calibration was prepared and measured before measuring the samples. After ten samples a quality control sample and a blank were injected to control the system stability. The achieved quantification range was 10–1000 ng/l.

qPCR data analysis

A custom R script, loosely based on the R "pcr" package of Ahmed and Kim42, was developed to create standard curves and determine relative quantity of each target based on the Ct values exported from the QuantStudio software. Linear model was fitted on the 10-point serial dilution Ct values and log10 transformed serial dilution quantities. Slope, intercept, R squared, and p-value were calculated, and standard curves plotted. Intercept and slope of the curve were then used to calculate relative quantities from the Ct values of each sample and each target. In the case when quantity normalization by another target is applied, the quantity of the target to be normalized was divided by the quantity of the reference target for that sample. Then, to meet the normality assumption of analysis of variance (ANOVA), box-cox power transformation was applied to the relative quantities using optimal lambda parameter. Finally, ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey test was performed to compare the differences between treatment groups and results graphed using box and whiskers plot and exported to the CSV file. Additional box and whiskers plot of raw Ct values was generated. In case of Arsenophonus, there were specimens in all treatment groups which tested negative for Arsenophonus. The numbers of negative samples per group were statistically compared using pair-wise Fishers exact test on a two-way contingency table as implemented in "rcompanion" R package. All R scripts described and used in the present study are available in the supplementary material as well as at the public GitHub repository (https://github.com/milenovic/rifampicin-qPCR-analysis-R). Finally, the ratio of relative quantities between males and females was calculated in Microsoft Office Excel by dividing the mean relative quantity of males by the mean relative quantity of females for each target and treatment group.

Results

Whitefly holobiont identity

PCR amplification of whitefly mtCOI gene fragment followed by sequencing produced identical sequences across 10 sampled individuals and yielded the sequence of 1175 bp. BLAST search against NCBI Nucleotide database showed 100% identity with MH205753.1 which is labelled as Bemisia tabaci MED Q2 mitochondrion. Subsequent phylogenetic analysis grouped our population closely with B. tabaci MED found in Cyprus, Israel, and Syria (Figure S3 of the supplementary material). Sequence obtained using Portiera specific primers (811 bp after trimming) showed 100% identity with several accessions, including the accession AB981341 which is Portiera group P1 according to Kanakala and Ghanim11. Sequence obtained using Rickettsia specific primers produced a trimmed sequence of 859 bp having 100% identity with accession KM386372, which is whitefly endosymbiont Rickettsia R1 group according to Kanakala and Ghanim11. Sequence obtained using Arsenophonus specific primers yielded a trimmed sequence of 425 bp. The top BLAST hit of this sequence was the sequence under the accession number FJ766366.1 with 97.88% identity. This accession is identified as B. tabaci Arsenophonus endosymbiont isolated from the population from Burkina Faso. As identical hit was not found, a phylogenetic analysis was performed. As shown in the Figure S4 of the supplementary material, Arsenophonus from this study groups closest to accession FJ766366 which is Arsenophonus group A2c according to Kanakala and Ghanim11. Despite being closest to the group A2c, phylogenetic analysis indicates that this Arsenophonus strain belongs to a distinct, previously undescribed subgroup. The produced Arsenophonus sequence is deposited to the GenBank database under the accession number OP289131.

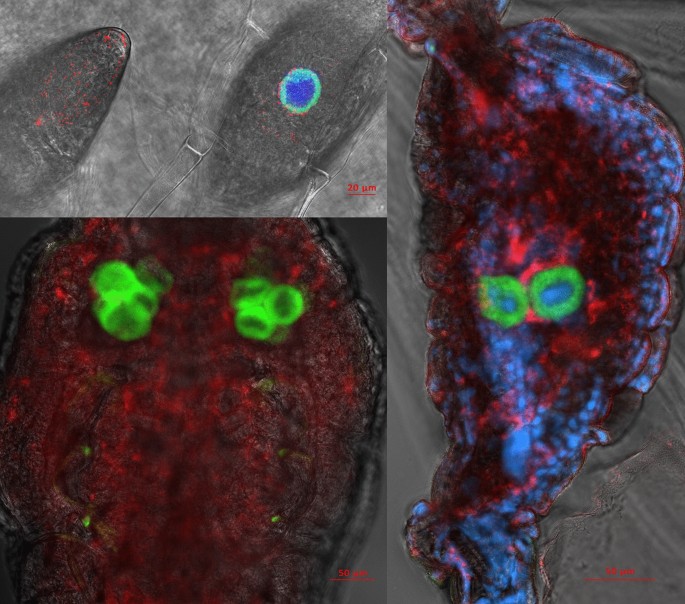

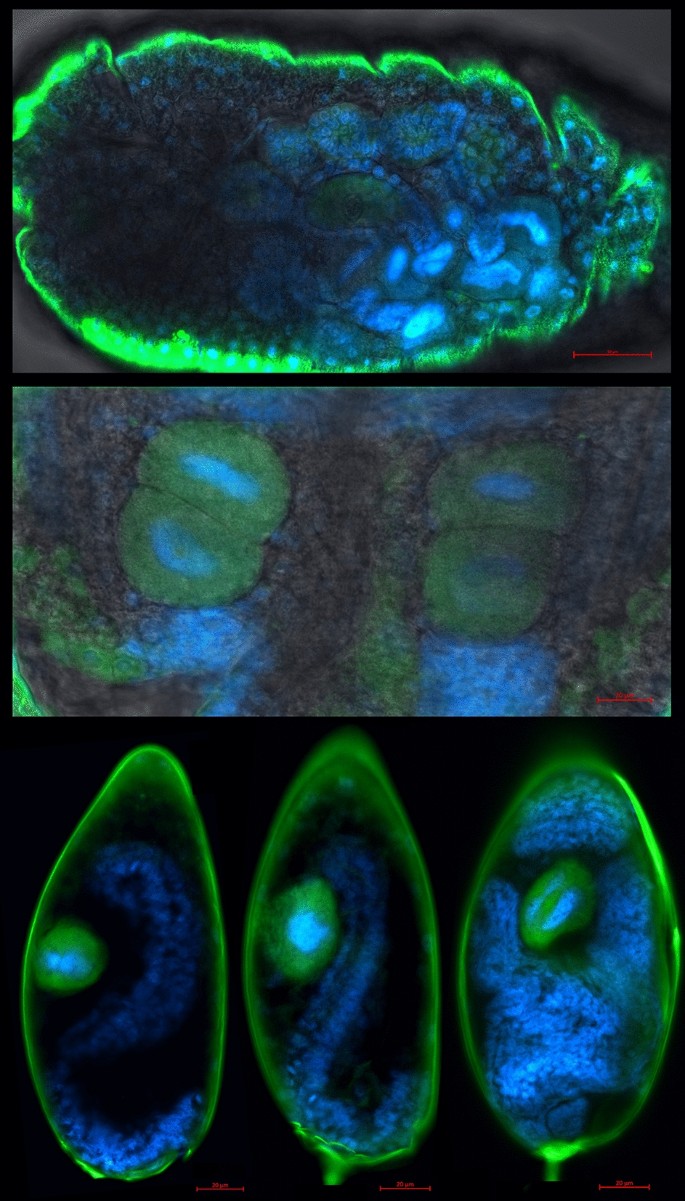

Localization of endosymbionts reveals typical bacteriocyte-confined phenotype for Portiera, while Rickettsia is localized primarily in haemolymph, but is also clearly present in bacteriocytes (Fig. 1). This was the case for all developmental stages, from the egg to adult. Novel Arsenophonus strain was localized to bacteriocytes (Fig. 2). Localization of Arsenophonus points towards very low densities of this endosymbiont in whiteflies, as the signal was barely detectable even with high laser power, high signal gain, and despite using doubly labelled probe which additionally increases the signal intensity.

Localization of endosymbionts Portiera (green) and Rickettsia (red) in whitefly eggs (top left), nymphs (bottom left), and adult abdomen (right) using fluorescence in situ hybridization with DAPI nucleic acid counterstain (blue). DAPI was not used in the nymph sample. The background grayscale image shows the transmitted light acquired using the transmitted photomultiplier tube (tPMT) detector.

Localization of Arsenophonus (green) in whitefly adults (top), nymphs (middle), and eggs (bottom three) using fluorescence in situ hybridization with DAPI nucleic acid counterstain (blue). Note the strong false signal around the edges of the samples caused by the refraction of laser light when passing through the cuticle. This artefact is especially pronounced here due to high laser power and gain that were required to detect low densities of Arsenphonus. The background grayscale image shows the transmitted light acquired using the transmitted photomultiplier tube (tPMT) detector.

Endosymbiont densities and effects of normalization

Standard curves used for relative quantification are presented in the supplementary material. PCR resulted in amplification of all targets in all ten dilutions, except for Arsenophonus, where the last dilution resulted in no amplification. Raw Ct values (Figure S2 in the supplementary material) give an overview of the quantities between the treatment groups and provide a rough indication of quantities between different targets. For all targets, a general pattern of lower Ct value can be observed in females than in males.

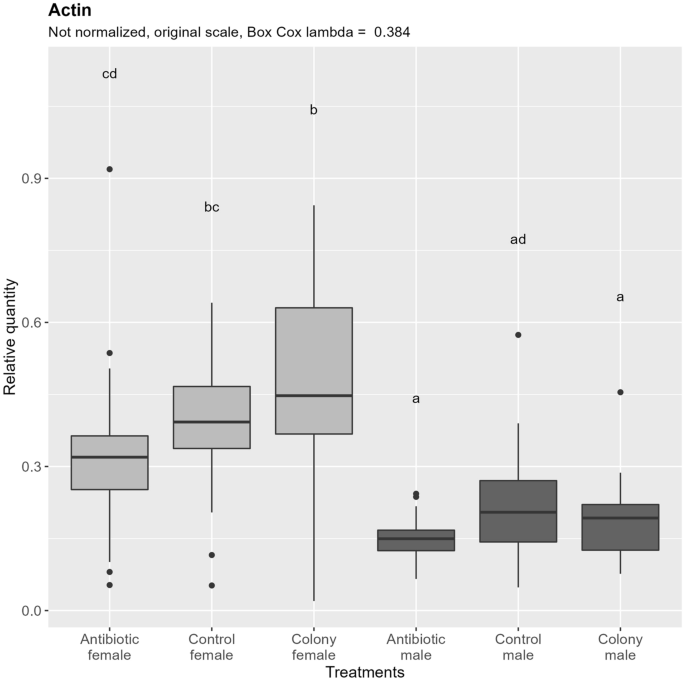

Quantification of nDNA (Fig. 3) shows significant differences between males and females, which nearly perfectly correspond to the theoretical double the amount of nDNA in females due to their diploid nature. Comparing between the treatment groups, no significant differences are observed between antibiotic treated and control groups in both males and females. No significant difference is observed between colony and control groups in both sexes. A difference can be observed in females, where nDNA content in the antibiotic treated group is significantly lower than in the colony, but not compared to the control. This difference could be explained by the different and uncontrolled age of the collected colony adults.

Relative quantification of nuclear DNA (Actin target) across the treatment groups. Note that the relative quantity is shown on the original scale for more intuitive interpretation, while the ANOVA was performed on the Box Cox transformed data. Values with the same letter are not significantly different (alpha = 0.05, Tukey's HSD test). Boxes represent the data between 25 and 75th percentile, horizontal line within the box represents median, and dots represent the outliers. A data point was considered an outlier as per the standard definition of the R package ggplot2 (when the data point (x) is either lower than Q1—1.5 * IQR (interquartile range) or greater than Q3 + 1.5 * IQR). Vertical lines extending the boxes (whiskers) are drawn using standard ggplot2 function and are calculated using the following formulas: upper whisker = min(max(x), Q3 + 1.5 * IQR), lower whisker = max(min(x), Q1—1.5 * IQR). IQR = Q3—Q1. Quantiles are calculated according to the default type 7 definition in R.

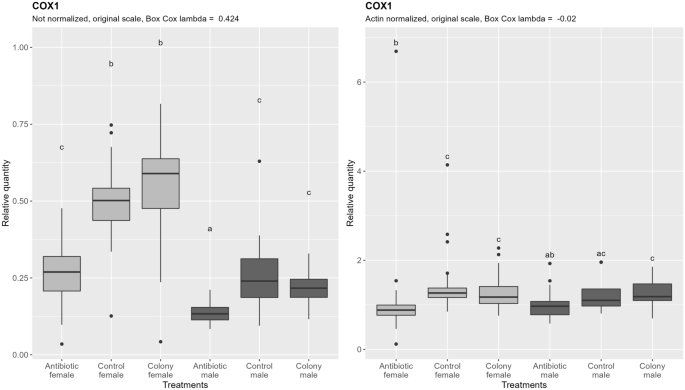

Quantification of mtDNA shows no difference between control and colony for both sexes, as in the case of nDNA, and similarly, about 50% less mtDNA is present in males. Antibiotic treatment affected the amount of mtDNA, as seen by a significant reduction of mtDNA in antibiotic treated groups, contrary to the case of nDNA (Fig. 4, left). If the ploidy influenced effect on mtDNA content is subtracted by normalizing the results by nDNA (Fig. 4, right), overall variability in the data is reduced, and the mtDNA content difference between control/colony and antibiotic treated groups remains in females, while it is not significant in males, although it does show a trend.

Relative quantification of B. tabaci mitochondrial DNA (COX1 target) across the treatment groups. Figure on the right represents quantities after normalization to the nuclear DNA, while the figure on the left shows the data without normalization. In both cases, ANOVA was performed on the Box Cox transformed data. Within one figure, values with the same letter are not significantly different (alpha = 0.05, Tukey's HSD test). Note that the relative quantity (y-axis) is shown on the original, not transformed scale for more intuitive interpretation. Definition of the boxplot is the same as in the Fig. 3.

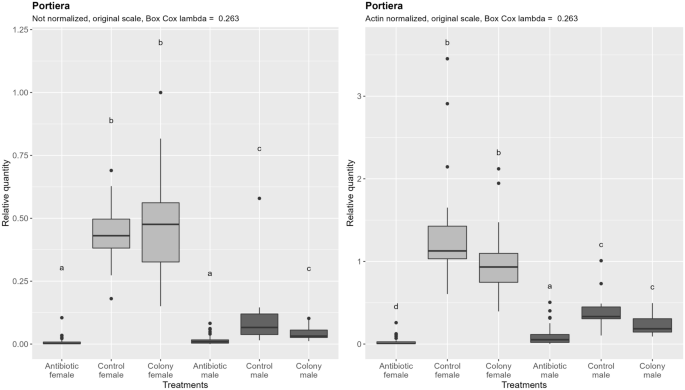

Quantification of Portiera densities reveals more striking significant difference between males and females (Fig. 5, left), which still remains after the subtraction of the ploidy effect, by normalizing to the quantity of nDNA (Fig. 5, right) on a per-sample basis. Antibiotic treatment caused a 129-fold reduction of Portiera in females and sixfold reduction in males when compared to the control (normalized data). After antibiotic treatment, there was no significant difference between males and females in not normalized data although a trend of lower densities in females is visible. After normalization, however, the significantly lower densities of Portiera in females compared to males are apparent. Taken together, there was a difference in the efficacy of rifampicin in reducing densities of Portiera between females and males. The densities of Portiera do not correspond exactly to the difference if nDNA content as it is the case for mtDNA.

Relative quantification of Portiera across the treatment groups. Figure on the right represents quantities after normalization to the nuclear DNA, while the figure on the left shows the data without normalization. In both cases, ANOVA was performed on the Box Cox transformed data. Within one figure, values with the same letter are not significantly different (alpha = 0.05, Tukey's HSD test). Note that the relative quantity (y-axis) is shown on the original, not transformed scale for more intuitive interpretation. Definition of the boxplot is the same as in the Fig. 3.

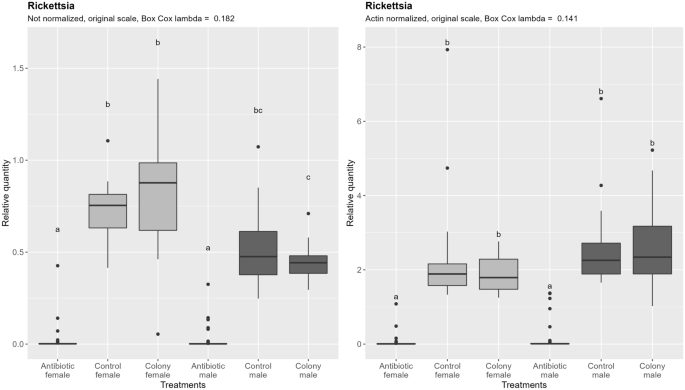

Contrary to Portiera, Rickettsia does not show significant different densities between males and females, although a non-significant trend to lower densities in males exists before the data are normalized by the nDNA content (Fig. 6). After accounting for the ploidy effect by normalization, the still non-significant trend is in opposite direction. Antibiotic treatment resulted in 297-fold reduction in females and 223-fold reduction in males compared to the control (normalized data). There was no significant difference between males and females after antibiotic treatment regardless of the normalization.

Relative quantification of Rickettsia across the treatment groups. Figure on the right represents quantities after normalization to the nuclear DNA, while the figure on the left shows the data without normalization. In both cases, ANOVA was performed on the Box Cox transformed data. Within one figure, values with the same letter are not significantly different (alpha = 0.05, Tukey's HSD test). Note that the relative quantity (y-axis) is shown on the original, not transformed scale for more intuitive interpretation. Definition of the boxplot is the same as in the Fig. 3.

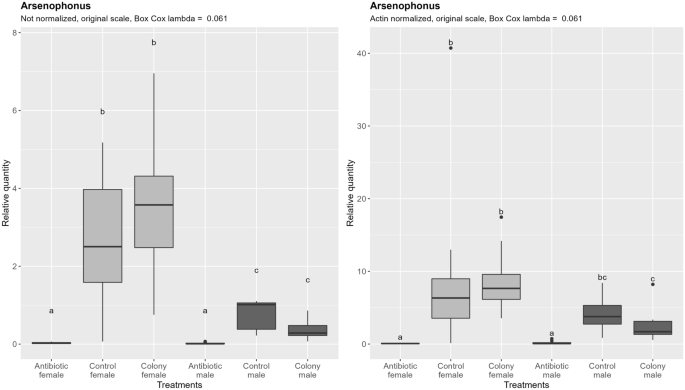

Arsenophonus densities are significantly higher in females in both colony and control groups (Fig. 7). The difference becomes less pronounced after subtracting the effect of ploidy level, and in the case of the control and antibiotic treated group it becomes statistically non-significant. Antibiotic treatment resulted in 87-fold reduction in females and 56-fold reduction in males compared to the control (normalized data). There was no significant difference between males and females after antibiotic treatment regardless of the normalization. Comparison of the proportion of Arsenophonus negative to positive reactions between treatments showed no statistically significant difference (Tables S1 and S2 in the supplementary material).

Relative quantification of Arsenophonus across the treatment groups. Figure on the right represents quantities after normalization to the nuclear DNA, while the figure on the left shows the data without normalization. In both cases, ANOVA was performed on the Box Cox transformed data. Within one figure, values with the same letter are not significantly different (alpha = 0.05, Tukey's HSD test). Note that the relative quantity (y-axis) is shown on the original, not transformed scale for more intuitive interpretation. Definition of the boxplot is the same as in the Fig. 3.

Microscopy observations of antibiotic treated individuals revealed much weaker signal intensity of Portiera, barely detectable signal of Rickettsia specific probe, and undetectable signal from Arsenophonus specific probe. Antibiotic treated nymphs and adults appeared paler in color (less pronounced yellow color) when observed under visible light stereo microscope. In antibiotic treated nymphs, there seemed to be more individuals with asymmetric or only one bacteriocyte present (data not quantified).

An attempt was made to produce the second generation from the antibiotic treated whiteflies on fresh, untreated plants. However, the efforts failed as only very few eggs were oviposited and these failed to develop.

Rifampicin detection

Presence of rifampicin was detected in both plant leaves before whitefly introductio...

Comments

Post a Comment